ALTHOUGH a constant stream of traffic passes by it every day, the Railway Pond is silent and somehow timeless – a watery oasis alongside a much larger sea of asphalt and modern-day housing development.

Located in the very jaws of the busy roundabout that links the B1018, Heybridge Approach, with two spurs of the A414 (one leading to the Causeway and the other to Spital Road), it looks like a survival from some kind of lost world – from a different time and place.

With the exception of the bypass edge, its reeded margin is protected by a tall curtain of well established trees and bushes that gently sway in the breeze.

In the warmer months the surface of its still water is just as green – covered by a blanket of duckweed.

It is, nevertheless, a “strictly ticket-only” fishery, occupied by tench, roach, crucian and ghost carp, where you will occasionally spot two types of angler – one of the human kind with rod and line, the other a more elusive, ashy-grey, day-fisherman, descended from an ancient lineage of unspoiled England.

Standing nearly four feet high, his official name is Ardea cinerea, but we all know him as the heron.

Rising on huge wings and with a distinctive kinked neck, he can be spotted slowly soaring and circling his domain – the Railway Pond.

There is no railway there now – it finally closed in 1966. However, the pond owes its origins to that much lamented branch line.

Opened in 1848 as the Maldon, Witham and Braintree Railway, in 1889 it was decided to extend it in the opposite direction to Woodham Ferrers (via West Station). This necessitated substantial engineering works, including a bow-string viaduct over the River Chelmer, numerous bridges and deep cuttings through glacial drift of the geologic age and loam underlying marine-formed London clay.

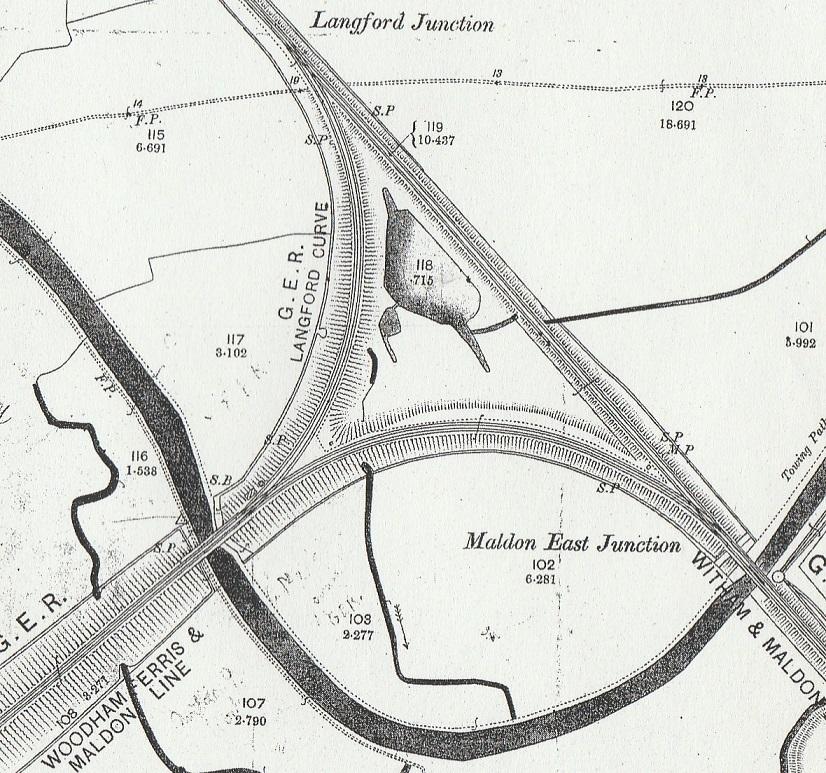

To link the two tracks together (East and West) with the Victorian-Jacobean East Station, a triangular junction (christened Langford Junction by the railway company) was created in the area of today’s roundabout.

However, the ground was far from level and certainly not at the required height. Tons of earth were, therefore, dug from a nearby “ballast hole” to rectify this and the result of that extraction was (and thankfully still is) the pond.

We know that the digging, largely by hand and involving a team of hard-working and hard-drinking visiting navvies of all ages and nationalities, took place throughout 1887 and 1888.

If the construction of the new line and the unintentional bonus of the creation of a pond weren’t special enough, it was what those navies found during their labour that has gone down in local history.

It has been spuriously stated by one historian that “Maldon owes nothing to the Roman influence”. But that isn’t quite right as the town’s older buildings are full of re-used Roman bricks.

Contemporary coins and pottery have also been found. However, there is no doubt that the major settlement area was in the Heybridge vicinity and evidence for that was exemplified by the digging of the Railway Pond.

In a later address to the Essex Field Club, an eye-witness described seeing “barrow-loads of pottery and other material” being recovered. Much of it consisted of different forms of the grey-wares of the Romano-British residents, but there were also large quantities of the finer and more exclusive Samian pottery, reserved for more sophisticated dining.

Not only that, but there were amphora storage vessels imported from far and wide, and many silver and bronze coins, from the reigns of Vespasian, Trajan, Augustus, Claudius, Nero and other emperors.

There were even enamelled brooches, pins, needles and spoons.

All in all it was a really important discovery and clear evidence of a densely occupied area of the former ‘civitas’, or ‘small town’, indicating long occupation both pre and post-conquest in date.

I would like to think that if the Railway Pond was being dug today, there would be an immediate stop placed on the work while a full archaeological investigation was undertaken.

That is exactly what did happen a hundred years later on the other side of the bypass at Elms Farm, with equally special discoveries, but this time in situ and in their proper context.

That site has since been professionally reported on, the finds conserved, analysed, some displayed and others properly stored for posterity.

Sadly that is not the case with the Railway Pond dig. For although you will find brief accounts of it in Fitch’s History of Maldon and the River Blackwater (published in 1894), volume three of the Victoria County History (1963) and the later Essex Archaeology and History transactions (1986), the bulk of the discoveries have disappeared, dispersed and lost over the passage of time.

Granted there are a few fragments in Colchester Museum, but they represent a miniscule sample of the “barrow-loads” that the navvies dug out.

Nevertheless, whenever I drive that way I always have a sideways glance at the pond and think about that exciting time all those years ago.

If I am lucky I might even see the grey fisherman on the wing and hear his distinctive, harsh “schaah” – a warning call to other birds that with the passing of both the Romans and the railway, this fascinating place is now his.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel