IT isn’t widely known, but Maldon was once renowned for clock-making and was the historic home to a number of very proficient horologists.

As far back as 1598, Abraham Johnson, probably a Dutchman, had settled in town and was making and selling bespoke timepieces.

More than a hundred years later, by 1703, John Draper had his business here and was producing distinctive and beautiful oak, long-case (or ‘grandfather’) clocks.

George Yates was doing the same thing in Maldon from around 1730, but the real heyday of the manufacture (as opposed to just the retail) of the Maldon long-case was between 1750 and 1820.

Researching that period, the names of the clockmakers come thick and fast – Frederick Richards was based in Maldon from 1749 to 1769, John Kimpton in the 1750s, William Francis in 1755, Thomas Bones 1758 to 1765, and Edward Hunsdon c.1761 to 1785.

Then we have Issac Death (he probably preferred to pronounce it as De’Ath) c.1772 to 1790, Robert Yeates 1782, Henry Pepper from 1787, William Daniel late-1780s to 1820, William Draper from c.1791, and John Payne, termed “clock maker and merchant” c.1796 to c.1835.

My favourite of them all during that peak Georgian era was one William Jeffries.

Born on November 20 ,1756, the son of a barber-cum-wig-maker, William was apprenticed to master clockmaker Richard Wright, of Witham.

He obviously did well under Richard’s tutelage, for the next we hear of him he is operating in his own name in Maldon.

Not only that, but he married Elizabeth Raven, of Hatfield Peverel.

Curiously, the happy couple tied the knot at St Dunstan in the West, in London’s Fleet Street – a church that boasts the first public clock in the city to have a minute hand.

Their wedding was on December 4, 1781, the same year that William was registered as one of Maldon’s clockmakers.

The young couple settled here and had at least two daughters; Ann Raven Jeffries (born in 1783) and Elizabeth (born 1785).

Clearly recognised as an important member of the business community, William Jeffries became part of the established structure when he was also appointed in 1787 to serve as overseer of the poor for the parish of All Saints.

His clock business went from strength to strength and William took on his own apprentices – firstly the previously mentioned William Daniel and then John Payne.

He also had his own High Street workshop and retail premises.

Housed in a former grocers, the 17th-century timber-framed building with a late 18th or early 19th-century brick façade that could have even been added by him, is today numbered 7 and 7a and is currently Beresfords, the estate agents.

It was in that building that you would have been able to hear the restful tick-tock of William’s products – the long-case, 30-hour hooded and birdcage wall-clocks.

While there would have been finished articles on display, you could have chosen a bespoke face or a special finish to the wooded case. Once the purchase was made, doubtless William (or one of his apprentices) would deliver the timepiece and perhaps even set it up for you.

William Jeffries died in Maldon in 1811, but his widow and daughters continued to sell clocks from the High Street shop and are listed as still doing this in the 1851 census – Elizabeth, aged 88, the two unmarried girls (Ann, 57, and Elizabeth, 55) and a young, 15-year-old servant, Eliza Boultwood, of Steeple.

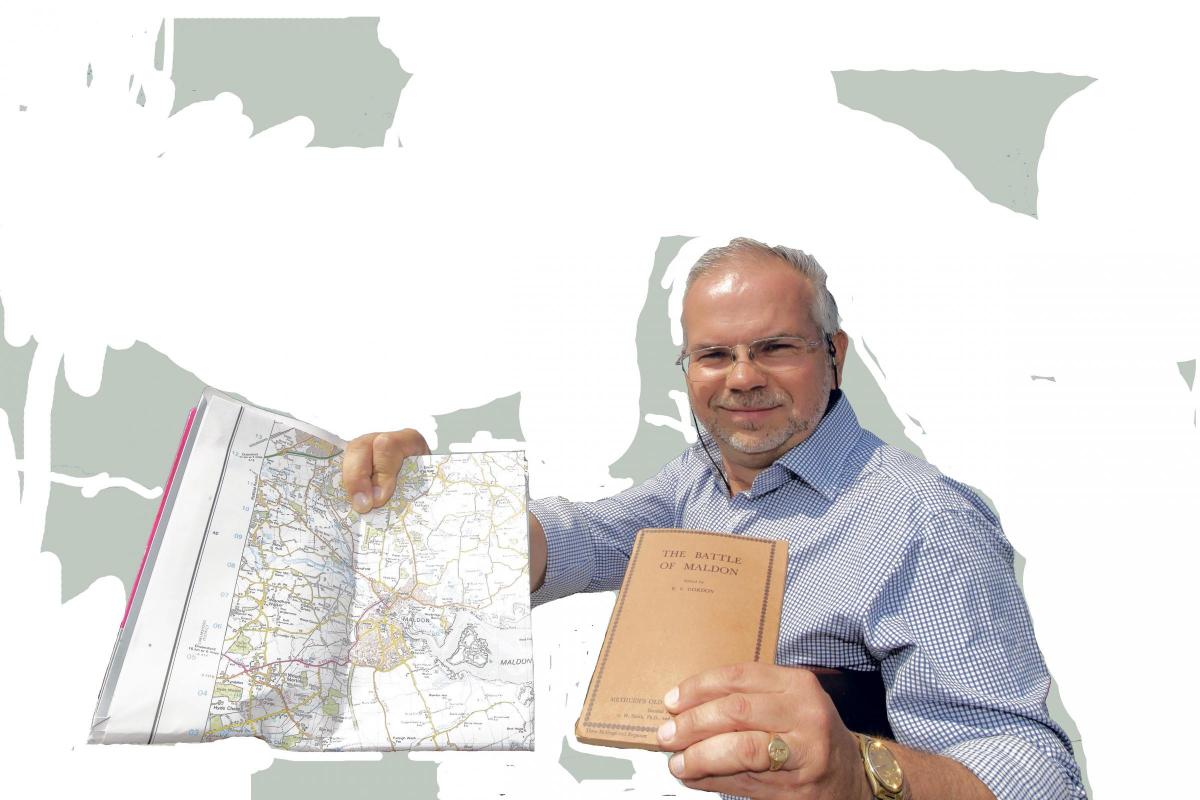

Although the market isn’t what it used to be, I really love grandfather clocks.

We only have a small house, but we have one in our front room, a late George III, mahogany eight-day, by Hepton of Northallerton (my wife’s home town in North Yorkshire) and another mahogany, eight-day, in the dining room – a “marriage” of mainly 1820 and named to “O’Brian of Liverpool”.

I have, however, always wanted a Maldon example and for many years envied a friend of mine who had a half a dozen or so.

Imagine my excitement then, when he recently offered to sell me one.

I jumped at the chance, of course, but then wondered where on earth we would put it. After a lot of head scratching we eventually found a space (on the landing) and in excited anticipation we duly collected the clock. The bonus was that it turned out to be a lovely example of William Jeffries’ work.

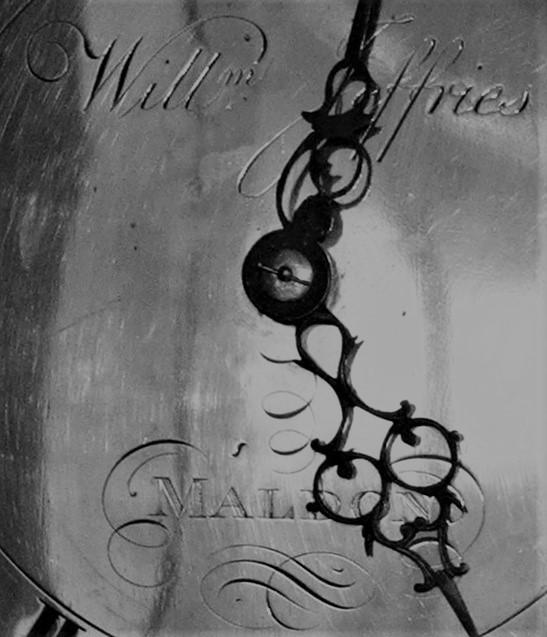

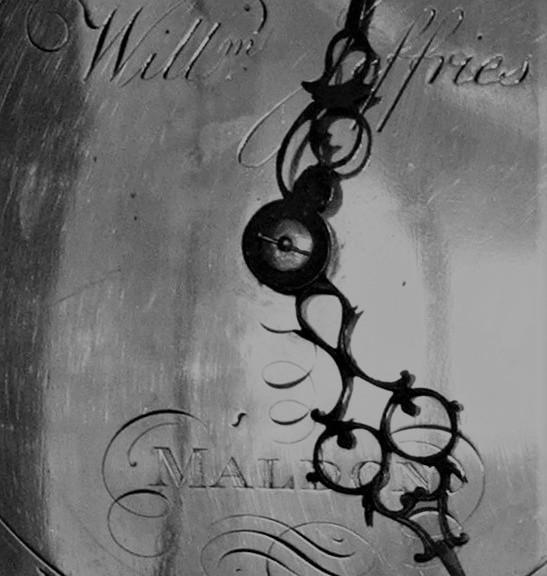

The 30-hour, oak long-case has a glass-fronted, pillared hood with three ball finials on top. Best of all, the brass face has the all important scrolled inscription on it – “Willm. Jeffries. Maldon”.

William’s craftsmanship shines through and has literally stood the test of time. As I listen to its melodic tick and the whirr and ding of its hourly chimes, it is somehow in itself a “timeless” thing.

Those sounds were born of William Jeffries hands, were heard by our Georgian ancestors and by successive generations of locals between then and now.

Maldon through time you might say and I am so pleased to be its latest custodian.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here